The Law “On Amendments and Additions to Certain Legislative Acts of the Republic of Kazakhstan on the Abolition of the Death Penalty” was signed by the President of the country, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, on December 29, 2021. This law completely abolished the death penalty, thus recognizing life imprisonment as the highest measure of punishment in the republic. Kazakhstan was moving towards this step gradually. So, in the Kazakh Khanate, according to Zhety Zhargy, capital punishment was given for murder, rape and incest up to the 7th generation. The death penalty existed in the Kazakh SSR for the first 13 years of the history of independent Kazakhstan. In 2003, the last death sentence was carried out in Kazakhstan, Twelve convicts were executed by firing squad. In 2004, an indefinite moratorium on the execution of death sentences, signed by the first President Nursultan Nazarbayev, came into force. In total, since 1990, 536 death sentences have been carried out in Kazakhstan.

The question of the admissibility of the death penalty as the highest form of punishment has caused and continues to cause numerous discussions. Both the abolition and its application are supported by various politicians and public figures, giving their weighty arguments. Kazakhstan took the side of the opponents of the death penalty, and therefore further – an analysis of 5 arguments in favor of the decision and 5 stories associated with them.

1. Dostoyevsky’s Argument: Violence Can’t Stop Violence

To date, there is no evidence that the death penalty is more effective in preventing crime than any other punishment. Let’s be honest, the death penalty is a murder with which the state wants to stop evil. But if evil tries to destroy evil, doesn’t evil win in the end? By killing a murderer, do we not become murderers ourselves? And in general, is it possible to kill for good?

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky, himself once sentenced to death, gave a detailed reflection on these questions in his “Crime and Punishment”, but at the last moment was pardoned and sent to hard labor in Siberia. Why did Rodion Raskolnikov kill the old pawnbroker, can you remember? A student and a freethinker, driven into a difficult situation by need and debt, he decides to commit a crime not for the sake of profit. The young man is driven by high aspirations, Raskolnikov wants to restore justice: get rid of the old, evil and stingy usurer and, thanks to her money, get his loved ones and “more worthy” people out of distress. “One death, and a hundred lives in exchange -it’s simple arithmetic!”, a remark he accidentally overheard echoes his theory. And now the ax is raised, Raskolnikov’s seditious idea gets the opportunity to test itself in practice. But instead of good comes solid evil. Together with the old woman, an accidental witness to the crime, Lizaveta, who herself suffered from the rough treatment of her usurer sister, falls under the axe. The money stolen by Raskolnikov turns out to be useless, he first hides it under a stone, and then indicates this place to the police. And in the very theory of Raskolnikov there is a “split”. Having imagined himself to be “those in power”, the arbiter of destinies, he transgresses the moral law, which leads to the moral degradation of his personality. Raskolnikov’s rebellion, directed against inhumanity, itself turns out to be inherently inhuman and immoral. “Did I kill the old woman? I killed myself,” the hero concludes desperately.

Dostoevsky’s work states that there is no evil for good. Evil does not destroy evil, it multiplies it.

Conclusion: The death penalty is murder, and a state that allows the death penalty legitimizes murder. There is no proven correlation between the use of the death penalty and a reduction in the level of crime, which means that when carrying out the death sentence, the state not only does not stop violence, but also legitimately enters a new murder into the criminal chronicles.

2. George Stinney’s Argument: The Cost of Judicial Mistake Too High

It is impossible to avoid mistakes. Despite modern advances in scientific and medical expertise, regardless of the procedural guarantees built into the judicial system, investigations are conducted by people, and people make mistakes. And, unfortunately, these mistakes happen much more often than many people realize, and their consequences are irreversible.

Fourteen-year-old George Stinney is the youngest suicide bomber executed in the 20th century in the United States. He was charged with the murder of two girls, Mary, 7, and Betty, 11. The defendant swore his innocence and did not let go of the Bible. However, the jury only had 10 minutes to sentence the black boy to death.

His parents were not allowed to see him, and the boy spent 81 days in solitary confinement awaiting execution. George Stinney was executed in the electric chair. The chair was disproportionate to the child’s body, the straps on his arms had to be tied instead of fastened, and in order for him to be at the right height, George was placed on the seat with the very Bible that he had brought with him.

In 2014, after reviewing new evidence, a US court overturned the death sentence 70 years after it was committed.

Conclusion: The death penalty might be charged to innocent people. At the same time, it is impossible to completely eliminate errors, and their consequences are impossible to correct.

3. Argument by Alessandro Serenelli: measures to prevent crimes must be humane

Maria Goretti is a saint widely venerated by the Catholic Church. An eleven-year-old girl was awarded the crown of a virgin and a martyr for resisting the coercion of her neighbor Alessandro to have sexual intercourse with her even under threat of death, and then forgave her murderer.

The sanctity of Maria Goretti is beyond doubt, but in this argument we will focus on Alessandro Serenelli. At the time of the murder, the guy was 19. Maria was poor and worked as a housekeeper in his family. Alessandro repeatedly tried to persuade her to have a sexual relationship, but this time he turned to action. Trying to take Mary by force, he threatened to kill her. The courageous girl said that she would rather die than commit a sin, to which Alessandro took out an awl and inflicted eleven blows on his victim. When Maria tried to get to the door, he hit her with an awl 3 more times, after which he fled. The victim was found and taken to the hospital, where she was operated on without anesthesia. Maria Goretti died the next day. Before her death, the girl forgave the killer and said that she wanted to see him with her in heaven.

Alessandro was captured by the police and sentenced to 30 years in prison. The guy did not repent of what he had done, until one day in prison he had a dream. He saw a beautiful garden and Maria Goretti walking in it. The girl came up and held out the lilies, which immediately burned in his hands. There were as many lilies as he struck her with an awl. The next morning Alessandro woke up a different person. He repented of his crime and wanted to change. He was released early, and after leaving prison, Alessandro found the mother of Maria Goretti to ask her forgiveness. “If my daughter was able to forgive you, who am I to deny you forgiveness?” – answered the mother of the murdered.

On June 24, 1950 Maria Goretti was canonized. Alessandro personally testified in favor of her beatification.

Subsequently, Alessandro Serenelli became a lay friar of the Order of Friars Minor Capuchin and served as a gardener at the monastery until his death. The lilies in his hands no longer burned.

“But not all criminals repent and reform”, many will object to this argument. This is true. But to give the criminal time to realize what he has done means to show humanity and mercy. We do not know what happens to the souls of executed criminals. Do they suffer forever for their atrocities, or does someone have time to repent, climbing the scaffold? Still, not to deprive the criminal of his life in retribution for what he did means to give him a chance for metanoia.

Conclusion: The principle of humanism should be realized in criminal law. The criminal law measures should not be aimed at the destruction of the offender, but at the suppression of the crime. Retribution is not justice. By imposing a death sentence, we permanently attach the stigma of a criminal to the condemned. By sentencing to imprisonment, we punish the crime, neutralize the threat to society and give the convict a chance for correction. And if he is a serial maniac and a degenerate, a person cannot be evil in the last instance. If this ultimatum belief in the human is the basis of the whole principle of humanism?

4. Christ’s Argument: the death sentence should not become a means of repressions

It is obvious that people who have committed especially grave offenses are sentenced to death. However, the composition of crimes worthy of death can vary greatly from state to state and prevailing ideology, and sometimes even be absurd. Thus, in modern Iran, the laws allow the death penalty for children – boys over 15 years old and girls over 9 years old. In Saudi Arabia, they are beheaded with a sword for hijacking an airplane, and in the DPRK, you can get a death sentence for hiding symptoms of Covid-19. It is impossible not to recall the Holocaust, when an entire nation was legally exterminated, and the Soviet past, when people were shot for their faith alone. The lists of victims of repression include such famous people as Joan of Arc, Maximilian Maria Kolbe, Thomas More, and once humanity condemned to death and crucified God himself.

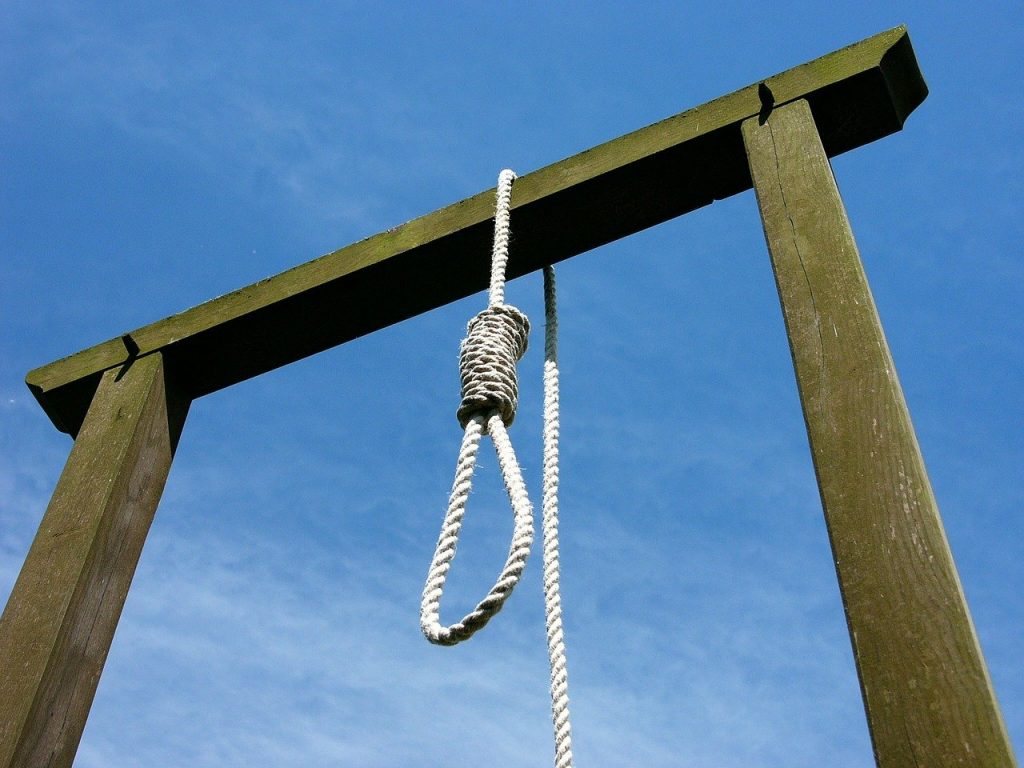

Conclusion: The guillotine in the hands of a state with absolute power can become an instrument of repression. Life imprisonment is a chance for the convict to receive amnesty when the government changes.

5. Pope Francis’ argument: “The death penalty is against the Gospel”

Pope Francis is an active adherent of the abolition of the death penalty. In October 2017, during the celebration of the 25th anniversary of the adoption of the Сatechism by the Catholic Church, the pontiff announced his decision to amend it. Human life “is always sacred in the eyes of the Creator, and therefore the death penalty is contrary to the Gospel,” the Pope explained.

Previously, the Сatechism did not exclude the use of the death penalty under conditions if “this is the only possible way to effectively protect people’s lives from an unjust aggressor”.

The new edition of article 2267 of the Catechism states: “Today, however, there is an increasing awareness that the dignity of the person is not lost even after the commission of very serious crimes. In addition, a new understanding has emerged of the significance of penal sanctions imposed by the state. Lastly, more effective systems of detention have been developed, which ensure the due protection of citizens but, at the same time, do not definitively deprive the guilty of the possibility of redemption”.

A special letter from Cardinal Ladaria to all the bishops of the Roman Catholic Church explains the meaning of the changes in the Catechism. He says that the development of the Catholic doctrine of the death penalty was the result of an evolution of faith, and emphasizes the need to create conditions for the abolition of the death penalty where it is still applied, through “respectful dialogue” with local authorities.

Conclusion: The rejection of violence in all its forms, the recognition of torture as unlawful and the abolition of the death penalty in criminal law are the result of the development of ethical thought in the process of the historical and cultural development of society. The abolition of the death penalty is a progressive step in line with the development of modern doctrine of faith and morality.

The abolition of the death penalty is a global trend. Commenting on the new draft law, Kazakhstan’s Ambassador to the Vatican, Alibek Bakaev, said that its adoption was due to “Kazakhstan’s desire to follow the democratic path that it has outlined for itself. The abolition of the death penalty is a response to the call of the entire world community, including the Pope. We are part of the world community, we want to be in harmony with the world community, so these steps have been taken”.

As of 2021, 144 countries have already abolished the death penalty in law or do not use it in practice.

“There is no place for the death penalty in the 21st century”, says former Secretary-General of the United Nations Ban Ki-moon. The world community, represented by the UN and other human rights organizations, continues to persistently urge the leaders of all countries to abandon its use, and October 10 has been declared World Day Against the Death Penalty.